Advertisers beware: Make honest claims – naturally

Why has the word ‘Natural’ become so relevant to marketers globally while marketing their brands across a range of food, beverages, cosmetics, baby care and personal care products? Why does the government feel the need to regulate the use of this word? Part 17 of the series of articles on Misleading Advertisements by Advocate Aazmeen Kasad, serves to demystify the use of this claim and provide an in-depth understanding of what the law on such claims are.

2020 will go down in history as the year of the COVID-19 pandemic and it has resulted in many lifestyle changes for people across the world. Many have adopted a healthier lifestyle, while several others who were already health conscious, have further strengthened their regime of consuming more products which serve to enhance their health.

Today, many consumers are looking for more ‘natural’ products across food products, baby care, personal care, household care and cosmetics, on account of greater knowledge of health, growing environmental awareness, trends set by the younger generation, etc.

Per a report by global consulting and research firm ‘Kline & Company’ in 2018, the “natural” trend is the most important trend in the personal care industry, leading traditional makers of personal care products, such as Unilever, Proctor & Gamble, Colgate-Palmolive to make a bee-line to acquire smaller companies and build their own natural divisions in order to compete with niche companies and start-ups in the industry.

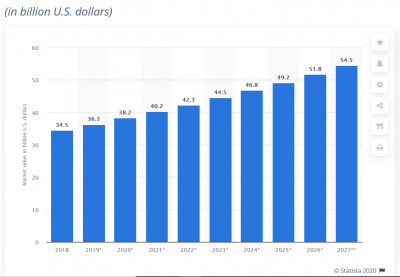

The timeline reports the global market value for natural beauty between the years 2018 and 2027. The global market value for natural cosmetics and personal care expected a positive increase from almost $34.5 billion in 2018 to roughly $54.5 billion expected for the year 2027. These data are a proof of the growing importance of the natural and organic beauty market. In fact, the awareness of consumers on the type of products purchased is growing over time. This is especially the case when it comes to personal consumer goods. In the specific case of cosmetics, an always bigger share of consumers tends to purchase natural and/or organic cosmetics. Cosmetics are considered natural with respect to two important dimensions: ingredients and processing. (Source: https://www.statista.com/statistics/673641/global-market-value-for-natural-cosmetics/)

The Global Natural Food & Drinks Market was valued at $79,137 million in 2016, and is estimated to reach $191,973 million by 2023, growing at a CAGR of 13.7% from 2017 to 2023. Natural food & drinks are minimally processed and free of artificial sweeteners, colours, flavours and additives like hydrogenated oils, stabilisers and emulsifiers. But there is no certification or inspection system to ensure that the label is accurate. Nonetheless, this market possesses high growth potential, owing to the fact that several food service providers, such as restaurants and hotels are inclined towards providing healthy food and drinks to cater to the needs of health-conscious consumers. (Source: https://www.alliedmarketresearch.com/natural-food-and-drinks-market )

India isn’t far behind with a large and growing segment of consumers demanding ‘Natural’ food, cosmetics, personal care products and baby care products.

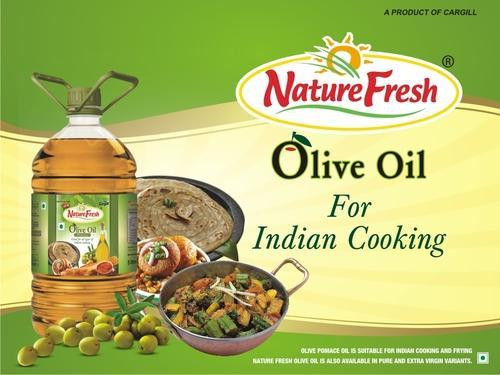

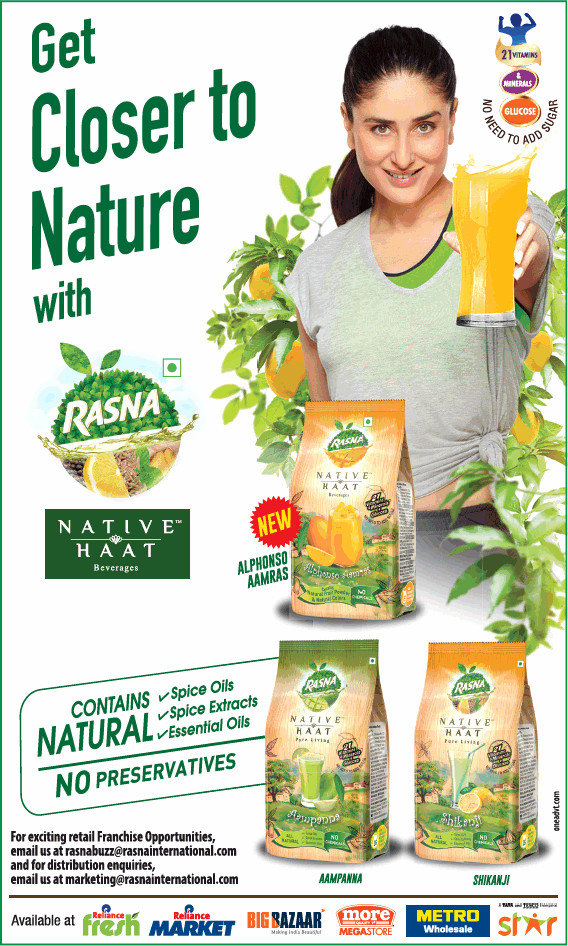

Marketers are well-aware of the demand for ‘natural’ flavours amongst the consumers. Several companies, have newly launched brands often use the word ‘Natural’ to reflect the need that finds favour amongst the target consumers, when they market their food products.

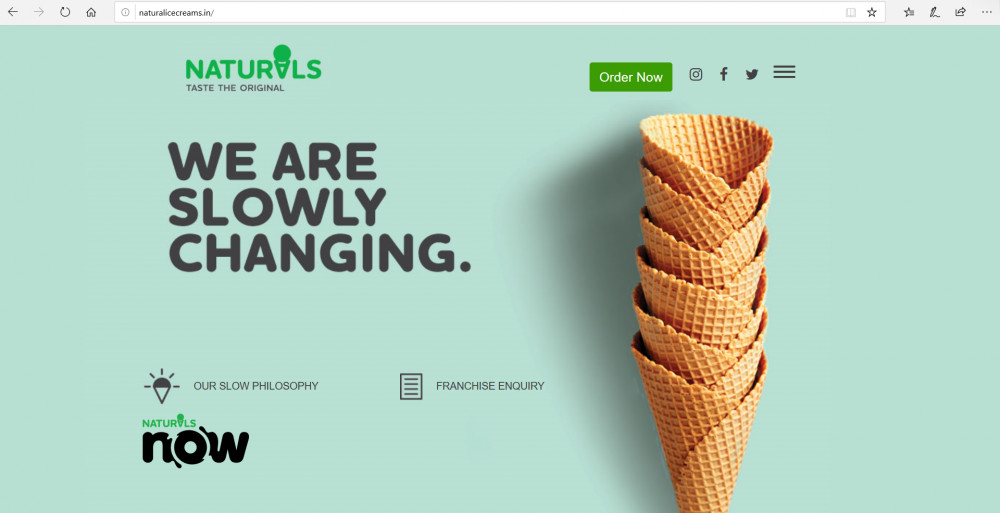

Established in 1984 in Mumbai, Natural Ice Cream claims to have been a pioneer in making artisan ice creams using only fruits, dry fruits, chocolates, milk and sugar.

Section 24 of the Food Safety and Standards Act, 2006 (the ‘Act’) provides restrictions on advertisements related to food and prohibits unfair trade practices in promoting the sale, supply, use and consumption of articles of food. The Act expressly prohibits an advertisement of any food which is misleading or deceiving or contravenes the provisions of the Act, rules and regulations notified under it.

The Act bars any false or misleading representation/ claims being made with respect to the standard, quality, quantity, grade composition, need for/ usefulness or any efficacy guarantee being made to the public unless it is based on adequate or scientific justification.

Per Section 53 of the Act, any person who publishes, or is a party to the publication of an advertisement, which (a) falsely describes any food; or (b) is likely to mislead as to the nature or substance or quality of any food or gives false guarantee, is liable to be fined up to Rs 10 lakh.

More recently, the FSSAI has brought into force the Food Safety and Standards (Advertising and Claims) Regulations, 2018 (the ‘Regulations’) which govern advertising and claims made by Food Business Operators, to prevent consumers from being misled. Food Business Operators are mandated to comply with all the provisions of these Regulations from July 1, 2019.

A “claim” is any representation which is printed, oral, audio or visual and states, suggests, or implies that a specific kind of food/ food product has particular qualities relating to its origin, nutritional properties, nature, processing, composition or otherwise.

Per the regulations, a claim may be made where a food is by its nature high or low or free of a specific nutrient provided the name of the nutrient or substance is preceded by the words ‘natural or naturally’ in the claim statement. Further, claims containing the adjectives “natural” shall be in accordance with conditions laid down in Schedule V and the claims containing words or phrases like “home-made”, “home cooked”, etc., which may give an erroneous impression to the consumer shall not be used.

Interestingly, as per Schedule V of the FSSAI Regulations, the claim “NATURAL” shall only be used to describe (a) a single food, derived from a recognised source viz., plant, animal, micro organism or mineral and to which nothing has been added and which have been subjected only to such processing which would only render it suitable for human consumption like: (i) smoking without chemicals, cooking processes such as roasting, blanching and dehydration and physical refining; (ii) freezing, concentration, pasteurisation, sterilisation and fermentation; and (iii) packaging done without chemicals and preservatives. (b) permitted food additives that are obtained from natural sources by appropriate physical processing.

The Regulation bars ‘composite foods’ from being described directly or by implication as “natural”, but permits such foods to be described as “made from natural ingredients” if all the ingredients or food additives meet the criteria in (a) and (b) above.

The above principles shall also apply to use of other words or expressions such as “real”, “genuine”, when used in place of “natural “in such a way as to imply similar benefits.

The regulation bars claims such as “natural goodness”, “naturally better”, “nature’s way”.

Certain food manufacturers don’t use the word ‘NATURAL’ as a claim. They include it as part of the brand or trade mark of the food product. The FSSAI has taken cognizance of the attempt to circumvent the law by such Food Business Operators.

Regulation 4 (7) provides that where the meaning of a trademark, brand name or fancy name containing adjectives such as “Natural”, etc., appearing in the labelling, presentation or advertising of a food is such that it is likely to mislead consumer as to the nature of the food, in such cases a disclaimer in not less than 3 mm size shall be given at appropriate place on the label stating that “*THIS IS ONLY A BRAND NAME OR TRADE MARK AND DOES NOT REPRESENT ITS TRUE NATURE”.

The disclaimer related to a claim shall be conspicuous and legible.

If an advertisement contravenes the provisions of the Act, but the label of the product accurately states the relevant information regarding the product, will the advertiser still be liable for the fine? The provisions of the section 53 of the Food Safety and Standards Act, 2006 states that the fact that a label or advertisement relating to any article of food in respect of which the contravention is alleged to have been committed contained an accurate statement of the composition of the food, shall not preclude the court from finding that the contravention was committed.

A number of processed food advertisers resort to Comparative Advertising. Advertisers should be cautious when resorting to comparative advertising to avoid being sued for unfair and dishonest/ misleading advertising. How does one ensure honest comparisons? There are several checks and measures that advertisers should ensure adherence to. The foremost is by comparing apples to apples. Invariably, advertisers risk their campaign by comparing apples to oranges. Most brands which indulge in such kind of advertising believe that they are safe by writing a disclaimer in a small font at the end of the advertisement. However, the courts have held a contrary view as most consumers believe what they see and hear in the advertisements. The small type disclaimers are illegible and seldom read by the consumers. Besides, a disclaimer cannot be used to correct a misleading claim in an advertisement nor contradict the main claim in the advertisement.

A number of Food brands engage celebrities to endorse their products. While there is no prohibition under any applicable law on using celebrity endorsements for food product brands, the celebrities/ endorsers should bear in mind the liability that can arise both under the Section 53 of the Food Safety and Standards Act, 2006 as also under the newly enforced Consumer Protection Act, 2019.

The Consumer Protection Act, 2019 introduces new provisions on ‘Misleading Advertisements’ and ‘Celebrity Endorsements’. The provision not only holds the advertiser liable, but the publisher of the false and misleading advertisement and the endorsers will also be equally liable for the same.

Having said that, the Act does provide certain defences for such parties. A party held liable can claim that the publication of the advertisement was done in the ordinary course of business without any knowledge of the fact that publishing the said advertisement would constitute an offence. Another form of defence available is that the person undertook all reasonable precautions and exercised all due diligence to prevent the commission of the offence; and that the offence was committed on account of an act or default of another person or reliance on information supplied by another person, etc.

Additionally, a new mechanism has been put in place by which complaints filed against a misleading advertisement shall be investigated and pecuniary penalties up to Rs 50 lakh shall be imposed on the advertiser if the advertisement is found to be false or misleading and up to Rs 10 lakh on the persons publishing the said misleading advertisements.

Per Section 2(1) of the Consumer Protection Act, an ‘advertisement’ means any audio or visual publicity, representation, endorsement or pronouncement made by means of light, sound, smoke, gas, print, electronic media, internet or website and includes any notice, circular, label, wrapper, invoice or such other documents. Therefore, this includes advertisements not only on the traditional media such as print, radio or television advertisements but also includes packaging, point of sale material, etc. Advertisements on the internet, including social media such as ads posted on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, LinkedIn, etc., also fall within the purview of the Act, as do advertisements on websites, which includes the advertiser’s own website(s).

A ‘misleading advertisement’ in relation to any product or service, is an advertisement, which (i) falsely describes such product or service; or (ii) gives a false guarantee to, or is likely to mislead the consumers as to the nature, substance, quantity or quality of such product or service; or (iii) conveys an express or implied representation which, if made by the manufacturer or seller or service provider thereof, would constitute an unfair trade practice; or (iv) deliberately conceals important information. Thus, any advertisement which expressly or impliedly misleads consumers about the product or service will also be considered as misleading in nature.

The Central Consumer Protection Authority will regulate matters relating to violation of rights of consumers, unfair trade practices and false or misleading advertisements which are prejudicial to the interests of public and consumers to promote, protect and enforce the rights of consumers. This Authority shall be headquartered in the National Capital Region of Delhi and may have regional and other offices across India.

A complaint relating to any false or misleading advertisements may be forwarded either in writing or in electronic mode, to any one of the authorities, namely, the District Collector or the Commissioner of regional office or the Central Authority. After a preliminary enquiry is made, if the Central Authority is satisfied that a prima facie case exists, an investigation shall be conducted.

Where the Central Authority is satisfied after conducting the investigation that the advertisement for which a complaint is received is false or misleading and is prejudicial to the interest of any consumer or is in contravention of consumer rights, it may, by order, issue directions to the concerned trader or manufacturer or endorser or advertiser or publisher, as the case may be, to discontinue such advertisement or to modify the same in such manner and within such time as may be specified in that order.If the Central Authority is of the opinion that it is necessary to impose a penalty in respect of such false or misleading advertisement, by a manufacturer or an endorser, it may, by order, impose on manufacturer or celebrity endorser a penalty which may extend to Rs 10 lakh: Provided that the Central Authority may, for every subsequent contravention by a manufacturer or endorser, impose a penalty, which may extend to Rs 50 lakh. Additionally, where the Central Authority deems it necessary, it may, by order, prohibit the celebrity endorser of a false or misleading advertisement from making endorsement of any product or service for a period which may extend to one year: For every subsequent contravention, prohibit such endorser from making endorsement in respect of any product or service for a period which may extend to three years. Where the Central Authority is satisfied after conducting an investigation, that any person is found to publish, or is a party to the publication of a misleading advertisement, except in the ordinary course of his business, it may impose on such person a penalty which may extend to Rs 10 lakh. The defence that the false or misleading advertisement was published in the ordinary course of business shall not be available to such person if he had previous knowledge of the order passed by the Central Authority for withdrawal or modification of such advertisement.

In light of the newly introduced provisions under the Act which came into force from July 20, 2020, it is advisable for both the advertisers and the endorsers to exercise caution in the claims that form part of the advertisement of the goods/ services. The ensuing Parts of the series will pertain to various aspects of what constitutes Misleading Advertising and key judicial precedents on the same.

Advocate Aazmeen Kasad is a practicing corporate advocate with over 20 years of experience, with a focus on the Media, Technology and Telecom industries. She is also a professor of law since 14 years. She is a member of the Consumer Complaints Council of the Advertising Standards Council of India. She is a speaker at several forums.

Share

Facebook

YouTube

Tweet

Twitter

LinkedIn